You are having trouble getting a special someone out of your mind. You want them. Now, forever, and always. Most importantly, you want them to want you.

You want them to think of you, even if only for a second, and feel the same kind of love and admiration that you do.

You are trying to study or read something, but even before you can finish a page, the thought of your beloved has distracted you more than four times already!

You just want to be with them, and that feeling makes it hard to do anything else. You can’t escape their spell, no matter what you do.

The image of their face smiling at you, the sound of their voice telling you they care, or the feel of their hand in yours could suddenly take over your mind and push everything else out.

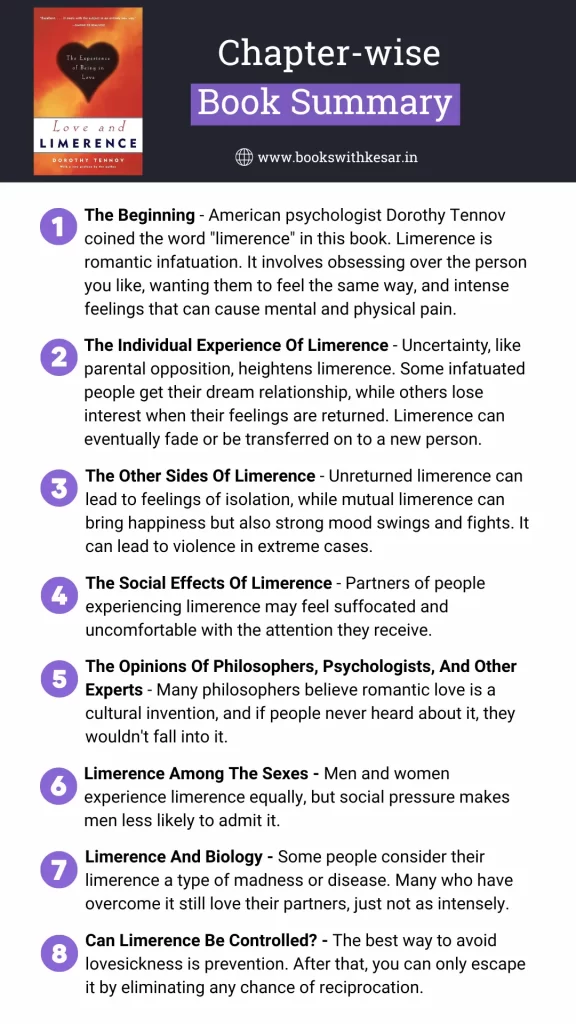

Does any of this sound familiar? In her book “Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love,” American psychologist Dorothy Tennov goes into detail about this subject.

In this book, which came out in 1979, Dorothy Tennov first coined the word “limerence.”

Tennov’s book seeks to answer the question of why people become so emotionally dependent on another person and how this can affect their relationships.

In this blog post, I have provided a detailed summary of every chapter of the book “Love and Limerence.” You may read it from start to finish or jump to any particular chapter you wish to revise.

Want This Book for Free? Start Your Audible Trial & Own Your First Audiobook—Even If You Cancel!

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Beginning

The author had always been curious about the subject of romantic love and found it strange that very few studies and books have researched this phenomenon adequately. She wanted to understand:

- What makes people fall in love?

- If some people are more likely to fall in love than others

- How often are people unhappy because of love?

- And how can we help them?

After learning about her interest in this topic, people came to her with their own stories of romantic love. She also read their diaries and conducted interviews with hundreds of people.

A big thing she learned was that many of the stories people told her were very similar. Each story was different, of course, in its own way.

Most of the time, they were full of dangers, decisions, partings, reunions, fights, jealousies, and regrets. Most also spoke of happiness.

Some of them were filled with pure, unforgettable moments of ecstasy. She heard stories that were as good as any grand saga.

They ranged from a three-day spree to a fifty-year longing that was never satisfied. She also heard life experiences from people who couldn’t understand these over-the-top exaggerations of romantic love.

- Fred broke up with Carol and spent hours thinking about her while lying in bed, calling her every few days until she told him to stop.

- Terry had loved someone since she could remember, even when she was a child. Many times, the person she is infatuated with doesn’t even know that she exists.

- Helen was confused by how romantic love was portrayed in the media, and her ex-husbands and lovers made her feel like she had to give them constant attention and be with them exclusively.

If the word “love” meant that there was genuine affection and care in a relationship, then the absence of love could be seen as a bad thing.

After all, Helen and others like her also had genuine affection and care for their partners. What they didn’t have was a need for their partner’s constant attention and intrusive feelings, which interfered with other aspects of their lives.

So the author decided that a new word had to be found, and she coined the word “limerence.” Limerence is what people usually mean when they say they are “in love.”

People who experience limerence are called “limerents.” People who don’t are termed “nonlimerents.” The person for whom you experience limerence is referred to as the “limerent object” (LO).

It looks like love and sex can happen without limerence, and any of the three can happen without the other two. The person who isn’t limerent for you may feel a lot of love and care for you, even tenderness, and maybe even sexual desire.

When it’s all said and done, a relationship that doesn’t involve limerence may be more important for you than any relationship in which you were limerent. Limerence is not the most important type of interaction between people, but when it is strong, it overshadows other relationships.

Watch Love and Limerence Chapter-wise Summary Video –

The Individual Experience of Limerence

Limerence starts off quickly and in a pleasant way. The way you see someone changes. It could be an old friend who you start seeing in a completely different light. Or it could be a new person—someone you didn’t know a week ago or even just yesterday.

No one has been able to figure out exactly why limerence occurs at one place and time and toward one person rather than another.

Some of the people the author spoke with fell in love at times when, from what they said, it was the last thing they thought about, expected, or even hoped for.

Even if it’s only imagined, it seems like the other person needs to do something, like look, say, or move in a way that could be taken as a hint that they might like you back.

Limerence is first and foremost a mental process. It is a way of looking at what happened, not the events themselves.

“Love is a human religion in which another person is believed in.” Robert Seidenberg

Limerence may start as a slight feeling of growing interest in a certain person, but it can grow into a very strong feeling if the right conditions are met.

Most of the time, it also goes down, dropping to zero or a low level. At this low level, limerence is either turned into something else or given to someone else, who then becomes the focus of a new limerent passion.

In the best cases, the feeling of limerence between two people fades as they get to know each other better, and at the same time, love grows. In either case, people agree that the state does not always remain the same.

Limerence is made up of a few important components:

- Obsessive thoughts about your LO, which could be a sexual partner or someone who doesn’t even know you

- a strong desire for reciprocation, wanting the LO to feel the same way about you

- dependence of mood on LO’s actions or, more precisely, your interpretation of LO’s actions in terms of the likelihood of reciprocation

- inability to react limerently to more than one person at a time (exceptions only occur when limerence is at a low state—early on or just about to fade)

- fear of rejection and uncomfortable shyness when around LO, especially at the beginning and whenever there is doubt

- intensification through adversity and obstacles (at least up to a point)

- a high level of sensitivity to any action that could be seen as positive and an extraordinary ability to come up with explanations for why the neutrality that an uninterested observer might see is actually a sign of hidden passion in the LO

- an aching of the “heart” (a region in the center front of the chest) when there is a lot of uncertainty

- a buoyancy (like walking on air) when it seems like LO feels the same way

- a general intensity of feeling that pushes other worries to the back of your mind

- a remarkable ability to focus on what is good about LO and not dwell on what is bad. You may even show compassion for what is bad and turn it, at least emotionally, into something else that is good

For the process to go all the way through, it seems like there needs to be some kind of uncertainty, doubt, or even threat to reciprocity. There is a lot of evidence that an obstacle from the outside, like the resistance Romeo and Juliet faced from their family and society, can also be helpful.

In fact, psychologists talk about “the Romeo and Juliet effect,” which says that parents who try to stop their kids from falling in love may make it stronger.

In fact, if the limerent declares their feelings too early or if the LO shows signs of reciprocation too soon, this could stop the full limerent reaction from taking place. Something must go wrong for strong emotions to take hold of you.

One of the interviewees, Teddy, said that his limerence got worse when Sue’s boyfriend, Gerald, showed up at the dance. Without Gerald and the threat he posed, the initial pleasantness might have stayed that way and not turned into limerence.

One of the worst aspects of limerence is intrusive thinking—not being able to stop thinking about your LO even when you try to concentrate on other things.

It’s not that other things make you think of LO but rather the fact that LO is always in your head, which shapes how you think about everything else. If a thought has never been linked to LO before, you immediately make the link.

You think about what LO would think of the book you’re holding, the movie you’re seeing, or the good or bad luck you’re having. You start to picture how you’ll tell LO about it, how LO will react, what you’ll say to each other, and what actions might happen because of it.

As you do the simple tasks that make up your daily life, you make complicated plans for what might happen in the future. You plan the next date over and over again, going over every detail of what you will do to look better in LO’s eyes.

What LO said and did stays crystal clear in your mind. You try to figure out what these words or actions could mean. It seems like every word and action is constantly up for review, especially those that could be seen as proof of a “return of feeling.”

With proof that LO feels the same way, you feel very happy, maybe even euphoric. You spend most of your time thinking about and rethinking what you find attractive about LO, going over what has happened between you and LO so far, and appreciating things about yourself that you think might have made LO interested in you.

As a limerent, your goal is clear from the fantasy that takes up almost all of your waking time: you want a “return of feelings”—the ecstatically blissful moment when LO gives you what you think is a clear sign that they feel the same way about you.

It seems that limerence grows and stays strong when there is a balance between hope and uncertainty. Fear of rejection can hurt, but it also makes you want something more.

Love is the most irrational of all emotions. It’s hard for a person who’s attracted to someone to believe that the other person doesn’t feel the same way and never will. As a result, the individual may spend a lot of time hoping before accepting that a rejection is genuine.

On the other hand, fear of rejection can make someone very sensitive, which can make it hard to read LO’s body language. The LO could be interested in you, but due to fear, both of you never took any action.

Is this sad state of affairs something that has to happen in love? It does seem important to limerence, which is why we need a new word for it.

Unfortunately, it seems like limerent demands are inherently contradictory, because showing too much affection too soon or in a clear way can kill a limerent response from the other person.

Limerence, not love, grows when lovers can’t see each other as often or when they are angry with each other.

Even if the limerent believes they are in love with LO, this is not the case. Love usually means caring about the well-being and feelings of the other person.

Limerence, on the other hand, calls for a return. You have to give up other things in your life to meet this all-consuming need, including caring about the well-being and feelings of your LO.

The Other Sides of Limerence

Many of the people said that no one, not even close friends, knew about their situation. It looks like a lot more people go through limerence than most people think.

Unreturned limerence is a state of relative isolation. While mutual limerents are on their way somewhere to enjoy being with each other, at least in the beginning.

When there is a known relationship, even if it is troubled, a lot of time is spent talking to each other. And even though they may get bored at some point, friends and family are usually there to listen, give advice, and sometimes offer sympathy and support.

Also, there are real things to tell them, not just stories about how the way limerents say things has hidden meanings that the listener can’t see.

Another factor in these cases was that the limerent person was unable to end the limerence by transferring their feelings to a more receptive LO, though this was tried in most cases.

Some of the people who went through a long period of limerence did eventually got what they wanted from their LO, even marriage.

Some people experienced the kind of change in feelings that they were afraid would occur if their LO ever truly responded to them in the way they desired. After reciprocation was attained, their feelings diminished rapidly, and they no longer wanted to be with their LO.

Limerence that isn’t returned enough in a love-sex relationship is the same as one that isn’t returned at all. Someone who has been married for 30 years but never feels completely certain, and whose limerence as a result remains intense, feels the same as someone who is not in any relationship with their LO.

If anything, mood swings from happiness to sadness and anger to gratitude are stronger in a relationship where both people are committed to and are limerent about each other.

Limerence is linked to different kinds of violence. Check the police records for numbers on accidents, murders, and suicides where it’s clear there was a limerent factor involved.

Such tragedies seem to be caused not by limerence itself but by limerence that has been blown up and twisted.

Limerence usually starts around puberty. Even before a specific person who could be the target of limerence shows up, the young person feels a feeling that can be described as wanting to be in love.

This ready-to-burst feeling can come out in a cloudburst of emotion as soon as a target is found.

Teenagers don’t always wait for a real person to fill in the role of LO. Instead, they may become limerent for well-known individuals, such as a musician or movie star.

The Social Effects of Limerence

One of the strongest limerent feelings is the desire to hide the condition from LO and other people as a necessary part of the “game” until reciprocation is certain and some commitment has been made.

However, one change in behavior that close friends and family are likely to notice is when the limerent stops going to their usual places.

As a limerent, you want to –

- be with LO

- be where LO is likely to be if the relationship doesn’t allow you to be with LO all the time

- Poor replacements for being with LO are:

- being alone and thinking about LO

- talking about LO

Limerence can make people act in ways that are almost anti-social. Extreme emotional instability, or mood swings, is another behavior that goes along with limerence.

It can happen so quickly that it seems like an instantaneous change from the happiness of real or imagined reciprocation to the sadness of real or imagined rejection.

Trying to improve yourself, especially in how you look, is one of the signs of Limerence that is hardest to hide. As the intensity of limerence grows, you begin to doubt your initial assumption that LO must think highly of you if they showed the first sign of liking.

When this happens, you may lose the first hope, which is a crucial component, and try to regain it by paying closer attention to your appearance and personal development.

Another thing that could happen is that you become very interested in and knowledgeable about whatever is important to LO. Most of the time, these interests are short-lived and only last as long as your limerence.

Nonlimerents unintentionally cause suffering that appears real but that they cannot comprehend. Their partner seems to have an insatiable need for attention, like no amount of attention is ever enough.

A nonlimerent woman described her experience with limerent men “They would call and ask what I was doing, even though I was doing something important to me that had nothing to do with them. They acted like everything I did had to involve them all the time.”

Interviewees who fit the nonlimerent pattern used the word “suffocation” many times in their reports.

Someone once said this about people who are “in love”: “They are always getting hurt, and you can never tell what will hurt them. I’ll have fun at a party, but on the way home, they will say something like, “Why did you ignore me all night?” Really, it’s driving me crazy!”

Most of the time, though, it is the limerent partner who ends the relationship, not the nonlimerent partner. A lot of the time, the break is followed by a “scene” that makes the nonlimerent person feel sad, upset, and alone.

Members of The Group were bothered by the pressures they felt in relationships with limerents when they weren’t limerents themselves. Both limerents and nonlimerents don’t like being the LO, especially if they don’t feel the same way.

Overall, 91 percent of The Group found it unpleasant to be LO in some way, 84 percent found it very uncomfortable or worse, and a full third checked “oppressive.”

The Opinions of Philosophers, Psychologists, and Other Experts

Many philosophers believe in the idea that love is just a feeling that comes from a culture that encourages or even forces it in some way. They believe that not many people would fall in love if they didn’t hear about its existence from others.

While the author believes that culture has something to do with any phenomenon, she doesn’t fully agree that love is the invention of culture. It doesn’t seem likely that you have to hear about love in order to feel it.

Most likely, the culture will have some effect on the LO, especially on the nonlimerent LO, who is more open to such effects because they are not under the limerent spell.

If limerence is looked up to in the culture, LOs will not only be more tolerant of limerents who insist on being exclusive, but they will also be more likely to act like limerents.

Another factor that needs to be taken note of is that the artificiality and limits of the societies in which people live corrupt them. Society keeps us from reaching our full potential, so most of us are “unfulfilled” creatures whose abilities have been dulled by the hard things we have to go through.

So, love, or more specifically, limerence, also provides much needed excitement in some people’s otherwise boring and monotonous lives.

But really, a love that does not allow you to be free of possessiveness is a deception, even if it is described in romantic, flowery language and is “passionate.”

Having self-confidence and self-respect are necessary for true love.

When the object of the emotion can’t be reached, it’s not love, because only strong people can really love, and it’s not a sign of strength to feel unrequited longing. Through a close relationship with another person, the goal of love is to become more of who you are.

How can you tell the difference between love and love addiction (limerence)?

Quite simply, love means:

- having a secure belief in one’s own value

- getting better because of the relationship

- staying interested in things and people outside of the relationship

- sharing interests that go beyond love

- and letting each other “grow” in an environment free of jealousy and possessiveness

In the social and behavioral science journals, there were reports of research about what kind of person falls into love addiction.

They believed that people with low self-esteem, more traditional views, less money, or whose lives seemed to be driven more by external than internal sources of motivation were more likely to be obsessed with love.

Limerence Among the Sexes

Based on the author’s research, it seems likely that about the same number of men and women experience limerence. But there is social pressure on men not to admit that they deeply love someone.

The difference in how many people of each sex accept that they have a love addiction can be explained by the cultural roles of men and women. For example, it is more acceptable for a woman to admit to emotional dependence than for a man.

Women’s rights activists state that the social situation of women is the cause of their pain and problems. There is nothing inherently or genetically different about women that makes them have stronger and sometimes more tragic reactions to love.

Instead, women’s social condition of living a life with few options outside of the main cultural stream is to blame.

Women have always been second to men in society because they have had to depend on men for their status, safety, and even their lives. If social options are limited for women, women have to be in love with a man, or at least pretend to be in love with a man, to live in society.

In fact, recent researchers have found that when the general happiness and emotional well-being of the sexes are related to marital status, the unmarried woman is the happiest and the married woman is the unhappiest. Men fall in between, with married men doing better than bachelors.

One more factor to be considered is that the word “love” could mean maternal love that women feel, which makes them more affectionate in general. Women are more likely to feel sympathy and compassion when they see other people in trouble, but this affection should not be mistaken for romantic love.

Limerence and Biology

Limerence feels like something you do of your own volition once it starts. You go willingly and gladly toward the joy it promises.

It’s only later that uninvited thoughts of LO come back, and suddenly your mind can’t think of anything else. Then, the only way to get through the long hours of love-sick daydreaming is to imagine a moment when you and LO declare love.

Most people who write about love talk about madness, and part of that madness is that the victim loses control. It’s true that not everyone thinks it’s illogical or weird, but even many strong supporters of love consider it a disease.

Most former limerents who have now recovered tend to agree. Those who were once obsessed with each other but now just love each other could say, “We were very much in love when we got married, and now we love each other very much.”

Similar experiences and involuntary behaviors between different people show that limerence is deeply rooted in our humanity, no matter what our cultures or lifestyles are.

Why did limerence emerge and persist? In other words, why were people who became limerent able to pass on their genes to the next generation? To understand why limerence occurs, we could look at what it causes people to do.

As we’ve already said, many actions caused by limerence are generally seen as socially undesirable or even disruptive. People often say that when a couple has limerence, they don’t want to be around other people.

It takes attention away from business, government, and even family matters and puts it on LO. Limerence intrudes.

But limerence desire always leads to mating, which isn’t just sexual activity but also a commitment, a shared home, a cozy nest built for ecstasy, reproduction, and, most of the time, raising children.

In many species, mates form bonds that help their offspring stay alive. Some way is needed to help people find potential partners who are good for them.

So from a biological and reproductive perspective, limerence has this advantage over someone who just might want a casual relationship and no marriage or kids from their lover.

Can Limerence Be Controlled?

Limerence for a specific LO terminates when one of the following events occurs:

- Reciprocation, in which the happiness of reciprocity is slowly mixed into a lasting love or replaced by less intense feelings

- Starvation, in which even limerent sensitivity to signs of hope is rendered ineffective in the face of an onslaught of evidence that the LO does not return the limerence

- Transformation, in which limerence is transferred to a new LO

Even though limerence is overvalued in movies and music, it is still looked down upon in those close to us, who may need our help and comfort but have no idea how to ask for them.

People often suggest a variety of ways to deal with being lovesick, like taking a hot bath, going on a trip to a faraway place, or giving yourself an unusual treat.

But such advice is seldom helpful, as all you do while doing such activities is think about your LO. Although, there does come a point in the healing process where these suggestions can actually help.

Another approach that sounds very reasonable is to list all of LO’s flaws, mistakes, and problems. Except that the main thing that makes this approach stand out is that it didn’t stop limerence.

The good things about LO seem super important to you, and the bad ones don’t, or they seem like something you can help them with.

Some books suggest writing in a personal journal with all your heart. But if you write a lot about LO and how it makes you feel, it could backfire and make the problem worse.

Understanding what limerence and nonlimerence are is important if we want to help people who have them. Knowing what the effects of limerence are and that there are people who aren’t limerent might reduce some cases of false hope.

Maybe the best thing you can do for yourself is to cut off all contact and any chance of contact with your LO, who isn’t responding.

The way the limerent person reacts can also give people who aren’t likely to become limerents hope for better relationships with them. As long as you think that everyone is a limerent or can easily become one, it is hard not to see a casual glance as a sign of limerent interest.

But now that you know there are people (and your LO might be one) who don’t fall in love, won’t fall in love, and don’t want to fall in love, but could maybe bond affectionately, you might lose hope and with it your limerence, or you might “settle” for affectionate bonding.

Even if limerence for a new LO makes you less likely to keep the same relationship you had with your spouse/current partner in every way, knowing that limerence is an involuntary reaction (at least after a certain point) should lead to:

- avoiding limerence whenever possible

- making it less likely for limerence to completely destroy the current relationship

- maybe promises made while limerent shouldn’t be taken as if they were sacred

Many interviewees said they wished they had acted differently earlier on. Nearly everyone thought that limerence could be stopped voluntarily if it were “caught in time.”

Prevention is the best way to make sure you don’t get lovesick in the first place. Once it has you in its grip, the only thing you can do to get out of it is to eliminate any chance of reciprocation.

What can you do about it if you are the nonlimerent LO? Limerence only has one answer: do whatever it takes to wipe out all hope.

Interviewees talked about how they would say things like, “I like you as a friend, but…” or, “I need some time alone to figure things out.” You can’t count on either of these vague statements to bring the needed relief.

Instead of trying to help by showing friendly compassion, which is often seen as a sign of “hope,” you must be determined not to send any signals that could be seen as signs of reciprocity. Let other people show kindness to the limerent. Unless you can stop the problem from getting worse, this will mean you have to end the relationship.

Now put yourself in the place of the limerent’s nonlimerent friend. You look for ways to help. You ask questions like, “How can I help?”

But the answer is that all you can do is sit there and listen, which gets boring and seems pointless. Really, no one is qualified to deal with an unhappy limerent, least of all a nice, well-meaning friend who is not a limerent.

⚡ Want to Get This Life-Changing Book at the Best Price? Check Amazon Now!

🔸 Buy on Amazon India (🛒 Trusted by Millions)

🔹 Buy on Amazon (US, UK & More) (📦 Fast Worldwide Shipping)

👉 This post contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you—thanks for your support!

💡 Enjoyed this summary? Support Books with Kesar by donating here.

📢 Never miss an update! All new summaries are now on Telegram—Join the Channel.

📚 Want more insightful reads? check out these articles next:

- Book Summary: When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön (All Chapters Explained)

- 5 Best Books on Anxiety

- Book Summary & Review: Don’t Feed the Monkey Mind by Jennifer Shannon

- Book Summary: Don’t Believe Everything You Think by Joseph Nguyen (All Chapters Explained)

- Book Summary: The Highly Sensitive Person by Elaine Aron (All Chapters Explained)